Difference-in-Differences (DiD) in Journalism and Communication Studies

How Difference-in-Differences (DiD) analysis is applied in recent journalism and communication research

The pursuit of extensive, continuous, and loosely institutionalized experimentation can be understood as a crucial policy mechanism in China's economic rise.

China's policy process is much more unpredictable than the legislative processes we encounter in constitutional democracies.

-- Sebastian Heilmann

China stands as a “Red Swan” challenge to the social sciences. This term describes China’s unexpected development trajectory that defies conventional wisdom and traditional models of political transformation. While “Black Swan” events are typically used to describe unpredictable outcomes, China’s case is termed a “Red Swan” due to the continued dominance of revolutionary red in the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) flag and political symbolism.

The “red swan” of China’s reform and economic progress, in the context of stagnation or collapse of other socialist regimes, may be attributed to the breadth, depth, and duration of its policy experiments. A recent paper by Shaoda Wang from the University of Chicago and David Yang from Harvard University has documented and analyzed over 650 policy experiments in China since 1980.

The study reveals a remarkable system: since the 1980s, the Chinese government has been systematically trying out policies – from carbon emission trading to tax reforms – in selected localities before deciding whether to implement them nationally. Through comprehensive analysis of 652 policy experiments initiated by 92 central ministries over four decades, Wang and Yang uncover fascinating patterns in how these experiments are conducted and evaluated.

The study documents three facts about China’s policy experimentation.

- First, policy experimentation sites are positively selected for characteristics such as local socioeconomic conditions.

- Second, the experimental situation during policy experimentation is unrepresentative. When participating in policy experiments, local politicians allocated significantly more resources to ensure the experiments’ success.

- Third, the central government showed limited sophistication in interpreting experimentation outcomes. They often failed to fully account for both the positive selection of sites and the strategic behavior of local officials.

What stood out to me in this research was its use of the Difference-in-Differences (DiD) methodology.The DiD approach allowed the researchers to establish robust causal links between China’s policy experiments and their observed outcomes.

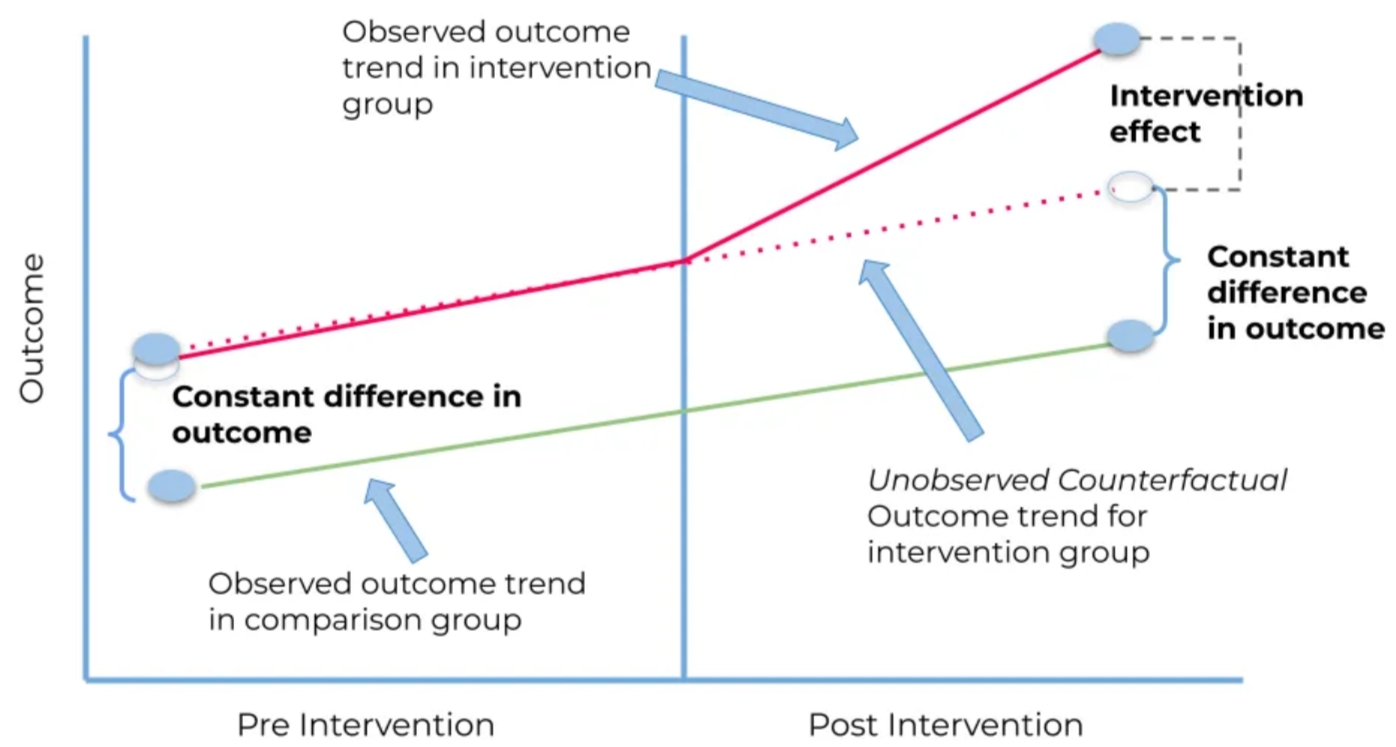

First, let me explain the fundamental logic of DiD and why it’s particularly suitable for this research. DiD is designed to estimate causal effects by comparing changes over time between a treatment group and a control group. The key assumption is that without treatment, both groups would have followed parallel trends. The “difference in differences” comes from subtracting two differences:

- The difference in outcomes before and after treatment in the treatment group

- The difference in outcomes before and after treatment in the control group

Source: Keisha (2022)

In Wang and Yang’s study, they apply this methodology in several sophisticated ways:

Basic DiD Implementation:

- Treatment group: Localities selected as experimentation sites

- Control group: Non-selected localities

- Treatment timing: The start of policy experiments

- Outcome variables: Local economic indicators (primarily GDP growth and fiscal revenue)

The authors go beyond basic DiD by employing a triple-differences approach to examine how local politicians allocate resources during experiments.

A triple-differences approach extends the logic of difference-in-differences (DiD) by adding a third dimension of comparison. While DiD compares changes between two groups over two time periods, DDD adds another layer of comparison that helps isolate the true policy effect more precisely. Let me break this down with Wang and Yang’s specific example: Their Triple-Differences Setup:

- First Difference: Time (Before vs. After experiment)

- Second Difference: Location (Experimentation vs. Non-experimentation sites)

- Third Difference: Policy Domain (Targeted vs. Non-targeted policy areas)

A Brief Introduction to Difference-in-Differences (DiD)

Difference-in-Differences (DiD) is a widely used econometric method for evaluating causal effects in observational studies, particularly when randomized controlled trials are infeasible. It is especially valuable in social sciences for analyzing the impact of policy changes, interventions, or events by comparing outcomes across treated and control groups before and after the intervention.

The core idea of DiD is simple: it leverages two dimensions of variation—time and group membership—to estimate a causal effect. Here’s a breakdown of the key components:

- Treatment group: The group exposed to the intervention or change.

- Control group: The group unaffected by the intervention, serving as a baseline.

- Pre-treatment period: The time before the intervention occurs.

- Post-treatment period: The time after the intervention is implemented.

DiD assumes that in the absence of the treatment, the difference in outcomes between the treatment and control groups would have remained constant over time. This is called the parallel trends assumption.

Source: Huntington-Klein

Mathematical Representation

Let’s denote:

- \(Y_{it}\): Outcome variable for group \(i\) at time \(t\).

- \(D_i\): Indicator for whether a group is in the treatment group (\(D_i = 1\)) or control group (\(D_i = 0\)).

- \(T_t\): Indicator for whether the observation is in the post-treatment period (\(T_t = 1\)) or pre-treatment period (\(T_t = 0\)).

The basic DiD regression model can be written as:

\[Y_{it} = \alpha + \beta D_i + \gamma T_t + \delta (D_i \times T_t) + \epsilon_{it}\]Where:

- \(\alpha\): Baseline outcome for the control group in the pre-treatment period.

- \(\beta\): Baseline difference between the treatment and control groups.

- \(\gamma\): Common time trend affecting both groups.

- \(\delta\): DiD estimate, capturing the treatment effect.

- \(\epsilon_{it}\): Error term.

The interaction term \(D_i \times T_t\) isolates the causal effect of the treatment by comparing the change in outcomes over time between the treatment and control groups.

Key Assumptions

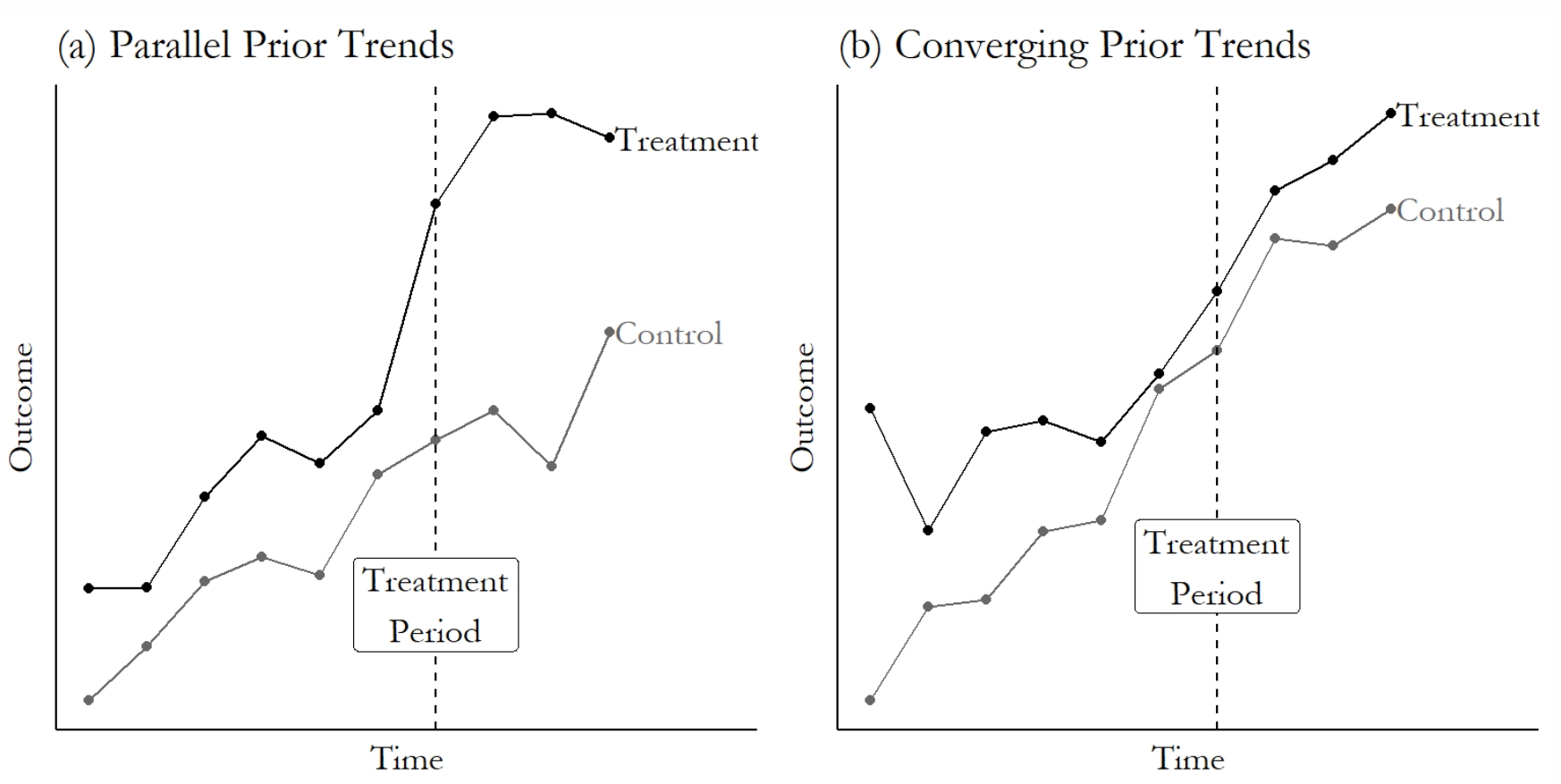

- Parallel Trends Assumption: In the absence of treatment, the treated and control groups would follow the same trend over time.

- No Anticipation: The treatment does not affect outcomes before its implementation.

- Stable Composition: The treatment and control groups remain comparable over time.

Applications of DiD in Journalism and Communication Studies

DiD has significant potential for Journalism and Communication research, particularly for evaluating the effects of policy shifts, media interventions, or events on information dissemination, audience behavior, or media environments.

- Policy Impact on Media Representation: For example, a study could examine how a new censorship policy in one region affects the tone or volume of media coverage compared to regions not subject to the policy.

- Digital Interventions: A researcher could analyze how introducing a fact-checking feature on a social media platform impacts misinformation spread, comparing the platform before and after the intervention to a similar platform without such a feature.

- Audience Behavior Studies: DiD can evaluate how events like major news outlet closures influence news consumption patterns in affected versus unaffected regions.

By isolating causal effects, DiD allows researchers in Journalism and Communication studies to move beyond correlation, offering robust insights into how policies and interventions shape media systems and audience dynamics.

Here are some examples.

The Influence of Media Ownership on Political Reporting

Archer, Allison M., and Joshua Clinton. 2017. “Changing Owners, Changing Content: Does Who Owns the News Matter for the News?” Political Communication 35 (3): 353–70. doi:10.1080/10584609.2017.1375581.

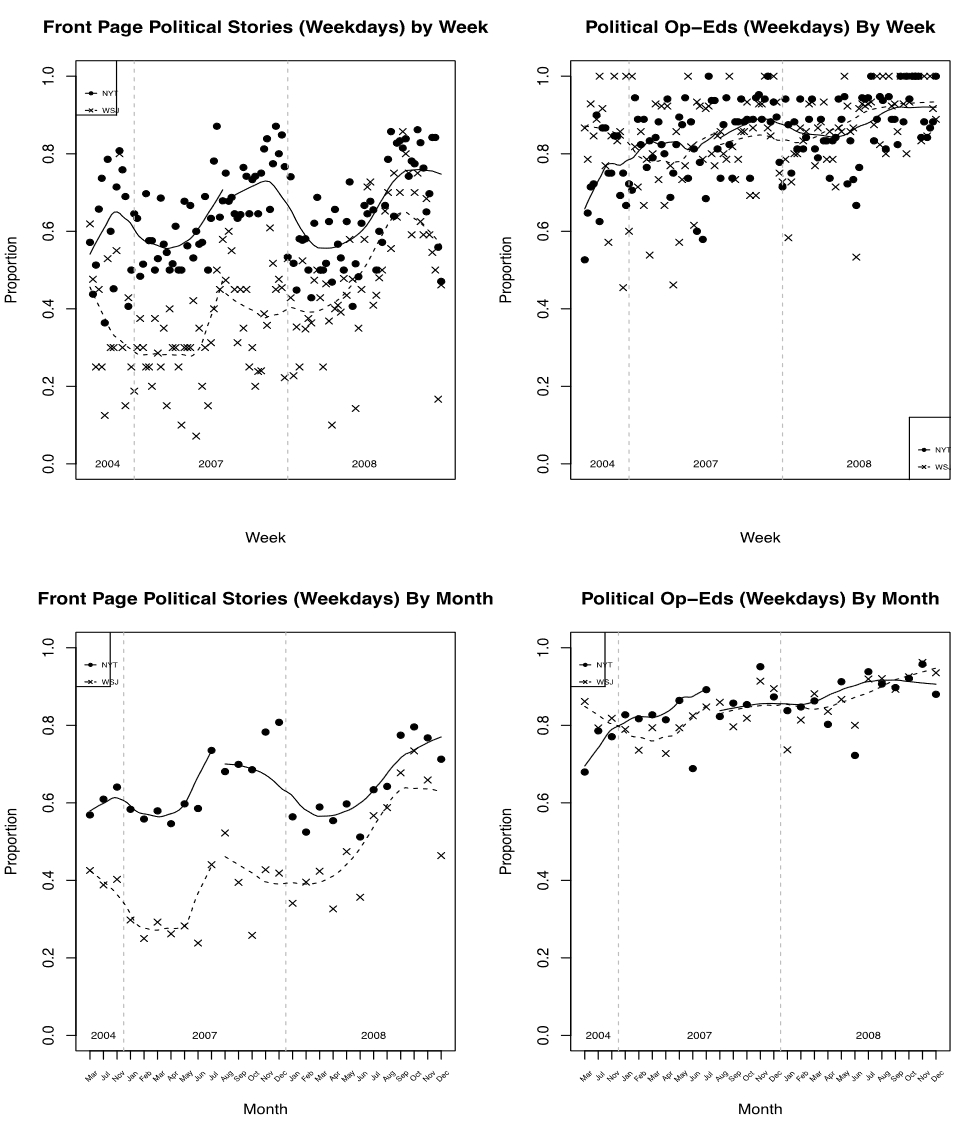

The article investigates the impact of Rupert Murdoch’s 2007 acquisition of The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) on its political content coverage, particularly compared to The New York Times (NYT), using a Difference-in-Differences (DiD) design. The authors analyzed 27 months of data, encompassing front-page and editorial content, to determine whether the ownership change influenced the newspaper’s political emphasis.

Key findings include:

- Increase in Political Front-Page Coverage: The WSJ’s political coverage on its front page increased significantly after the acquisition, closing the gap with the NYT.

- Editorial Pages Remained Stable: Political coverage in WSJ editorials remained consistent, indicating a targeted change in front-page reporting.

- Comparison with Peers: Additional analysis comparing WSJ with USA Today and The Washington Post reinforced the conclusion that the change in coverage was unique to WSJ, beyond general news trends or the 2008 presidential election.

The authors leveraged a Difference-in-Differences design to compare the coverage of the NYT and WSJ over time.

Comparison Groups

- The New York Times served as the primary comparison group. Both newspapers are headquartered in New York City, targeting similar audiences, making them ideal for DiD analysis.

- Additional comparisons with USA Today and The Washington Post provided robustness.

Design

- Pre- and Post-Intervention Periods: Coverage before and after Murdoch’s acquisition was analyzed, with the “intervention” defined as the ownership transfer in August 2007.

- Outcome Variables: The percentage of political stories on the front page (and above the fold) was compared across newspapers and time periods.

Regression Analysis:

- The authors used regression models with fixed effects to control for unobserved, time-invariant factors and news-cycle effects. They included interaction terms (e.g., “Murdoch × WSJ”) to capture differential changes attributable to ownership.

This figure plots the proportion of political stories and editorials appearing in the weekday papers of the WSJ and NYT across time – the top row graphs the trends for frontpage political stories by week and month and the bottom row depicts the trends for signed editorials.

The patterns evident in the figure reveal that the relative percentage of political editorials did not significantly change following Murdoch’s purchase of the WSJ – likely because both papers were already publishing such a high proportion of political editorials.

The Relationship Between the Decline of Local Newspapers and Changes in Federal Public Corruption Prosecutions (PPC)

Usher, N., & Kim-Leffingwell, S. (2024). How Loud Does the Watchdog Bark? A Reconsideration of Losing Local Journalism, News Nonprofits, and Political Corruption. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 29(4), 960–982. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612231186939

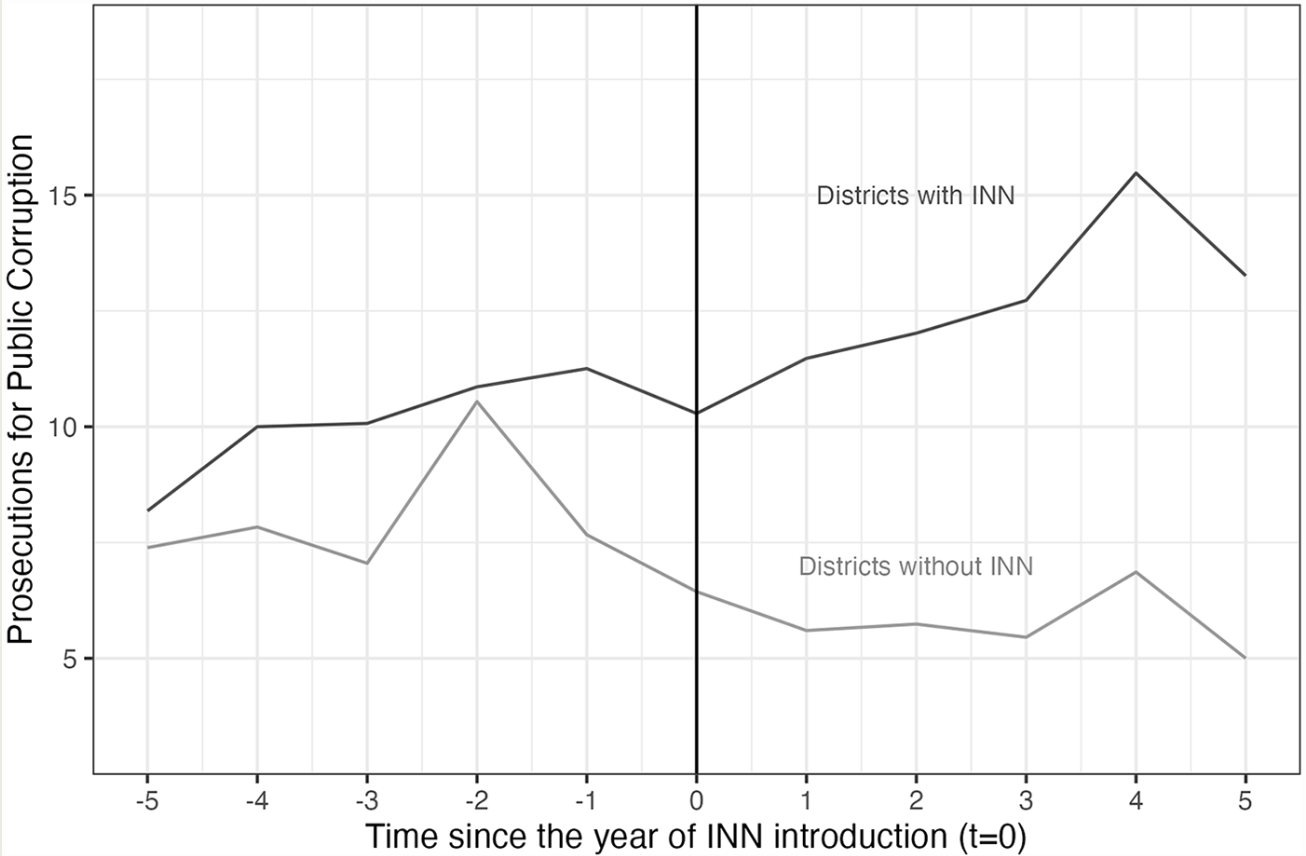

The article examines the relationship between local journalism, particularly nonprofit news, and public accountability as measured by federal prosecutions for public corruption (PPCs). It employs a Difference-in-Differences analysis to assess the impact of nonprofit news interventions on judicial districts where nonprofit outlets are introduced.

The study investigates:

- The correlation between declines in traditional local journalism (newspaper employment and circulation) and reductions in PPCs.

- The potential of nonprofit news organizations to mitigate declines in watchdog journalism and influence accountability outcomes.

Findings include:

- A mixed relationship between reductions in local newspaper employment and PPCs.

- A positive association between nonprofit journalism presence and increases in PPCs, suggesting that nonprofit news outlets enhance public accountability.

The article employs DiD to measure the causal effects of nonprofit news interventions on corruption outcomes:

Treatment and Control Groups:

- Treatment Group: Judicial districts where nonprofit news outlets affiliated with the Institute for Nonprofit News (INN) were introduced.

- Control Group: Districts without INN-affiliated nonprofit outlets.

Pre- and Post-Intervention Periods:

- The year a nonprofit outlet was introduced marks the intervention point.

- Outcomes were analyzed for 5 years before and after the introduction to assess short- and medium-term effects.

Key Variables:

- Dependent Variable: The number of PPCs within a judicial district.

- Independent Variables: Introduction of nonprofit outlets (binary for presence and continuous for timing), newspaper employment, and circulation data.

- Controls: Population, GDP per capita, and court efficiency.

Parallel Trends Assumption:

- The authors verified that pre-intervention trends in PPCs were similar across treatment and control districts, supporting the validity of the DiD approach.

Figure 1 describes the divergence in average PPCs between districts with and without INN member outlets before and after an introduction of new INN membership (t = 0). The trend lines first show parallel trends before the intervention of new INN membership. They are relatively stable but increasing in the number of PPCs across the two types of districts, except for a sudden bump in (t − 2) within districts without INN members, followed by a decrease in PPCs right before the intervention. Such trends begin to diverge in t = 1, where PPCs increase in INN districts and decrease in districts without INN members. This divergence continues in the following years, widening the gap between the two district types.

Newspaper-Politician Collusion and its Impact on Political Coverage (Media Independence)

Balluff, P., Eberl, J.-M., Oberhänsli, S. J., Bernhard-Harrer, J., Boomgaarden, H. G., Fahr, A., & Huber, M. (2024). The Austrian Political Advertisement Scandal: Patterns of “Journalism for Sale”. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19401612241285672. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612241285672

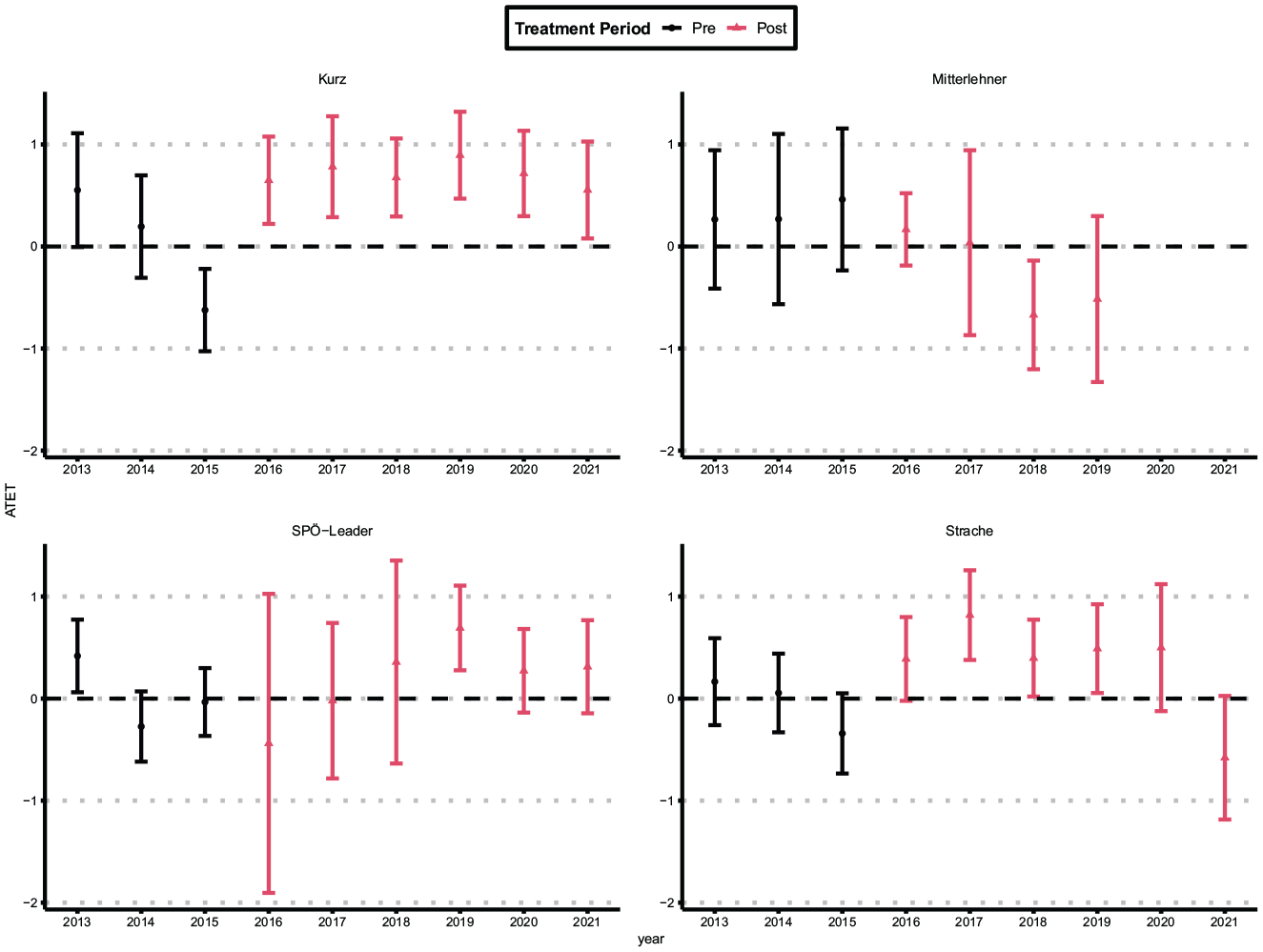

This article investigates the so-called “Inseratenaffäre”, a 2021 Austrian political scandal in which then-chancellor Sebastian Kurz allegedly colluded with the tabloid newspaper OE24 to receive favorable news coverage in exchange for government institutions buying advertising in the paper. The authors use automated content analysis on 222,659 political news articles from 17 prominent Austrian outlets between 2012-2021.

Employing a Difference-in-Differences (DiD) approach, they find

- The former chancellor’s visibility increased far more in OE24 after 2016 compared to other outlets and politicians.

- OE24 didn’t necessarily become more positive toward the chancellor, but became more negative toward his political rivals.

By comparing the DiD estimates for Kurz to other major politicians, they demonstrate the effect is specific to Kurz, further strengthening the link to the scandal allegations.

-

Treatment and control groups: OE24 is considered the “treated” outlet that allegedly received bribes. The other 16 outlets serve as the “control” group for comparison.

-

Pre and post-treatment periods: 2012-2015 is the pre-treatment period before the alleged bribes began. 2016 onward is the post-treatment period.

Outcome variables

- Visibility: Measured by the count of an politician’s mentions aggregated to the monthly level for each outlet. Log-transformed to capture percentage changes.

- Favorability: Measured by sentiment scores from a fine-tuned language model, aggregated at the article level.

The graph makes it easy to see the stark difference between the results for Kurz and the other politicians. For Kurz, there is a clear and substantial jump in the treatment effect starting in 2016, indicating that his visibility in OE24 increased dramatically compared to the control outlets after the alleged scheme began. In contrast, the ATETs for the other politicians remain close to zero and statistically insignificant, suggesting they did not experience a similar boost in visibility.

Decline of Local Newspapers Affects Political Polarization

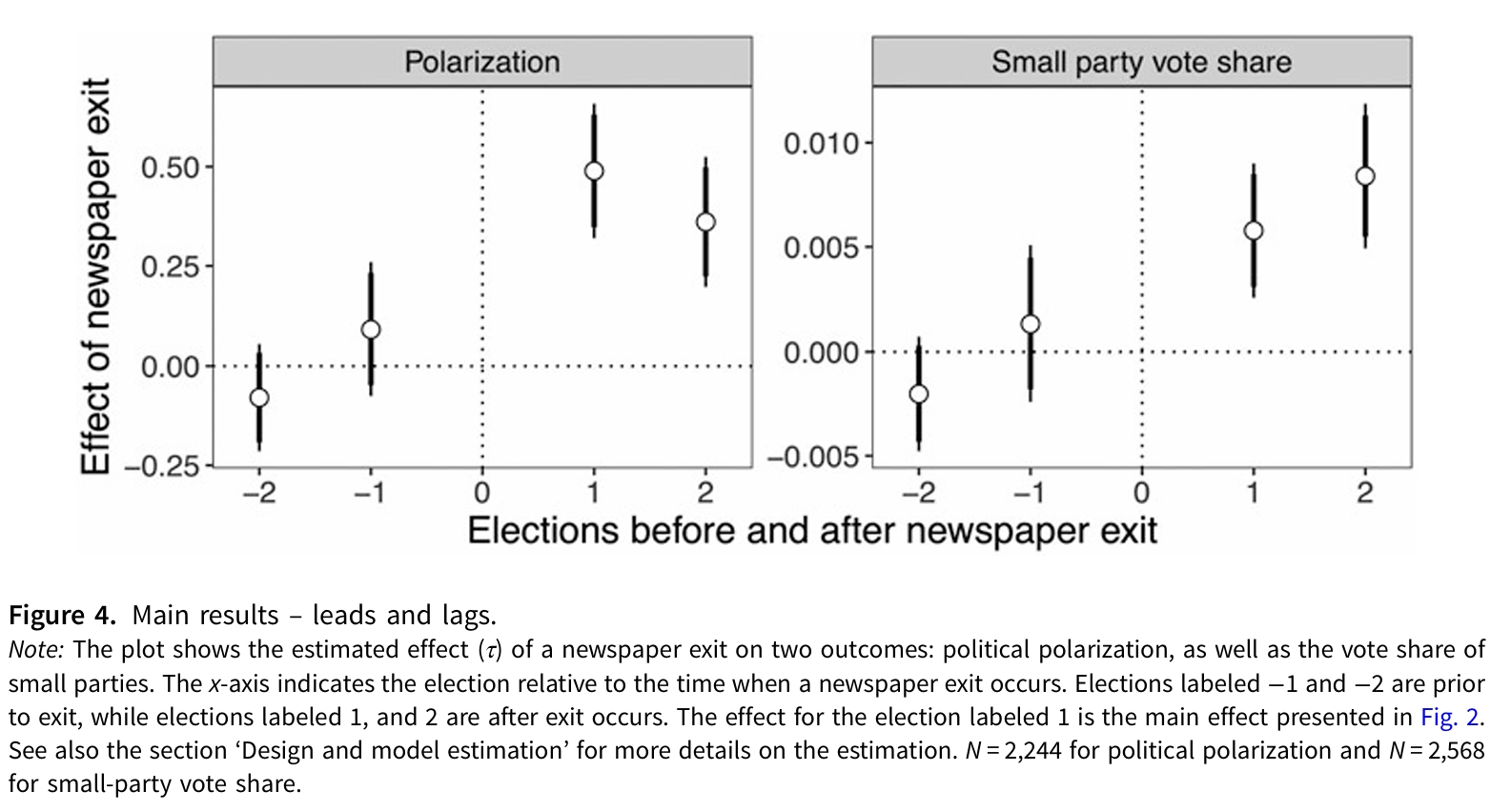

Ellger, F., Hilbig, H., Riaz, S., & Tillmann, P. (2024). Local Newspaper Decline and Political Polarization – Evidence from a Multi-Party Setting. British Journal of Political Science, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424000243

The study examines how the decline of local newspapers in Germany between 1980-2009 affected political polarization, as measured by electoral outcomes. It combines data on local newspaper exits, county-level electoral results, and a large annual media consumption survey.

To estimate the causal effect of local newspaper exits, the authors employ a difference-in-differences (DiD) research design:

Treatment and Control Groups:

- The treatment group consists of counties that experienced a local newspaper exit during the study period.

- The control group consists of counties that did not have a local newspaper exit.

Pre and Post-Treatment Periods:

- The study period covers federal and municipal elections in Germany from 1980 to 2009.

- The authors examine changes in political outcomes over time, comparing the treated counties to the control counties.

DiD Estimation:

- The authors measure the change in political outcomes (e.g., electoral polarization, small party vote share) within each county over time.

- They then compare the changes in treatment counties (those with a local newspaper exit) to the changes in control counties (those without an exit).

- This difference-in-differences approach allows them to isolate the causal impact of the local newspaper exit, accounting for any time-invariant differences between counties.

Dynamic Effects:

- The authors also estimate dynamic effects, looking at how the impacts of local newspaper exits evolve in the elections leading up to and following the exit.

- This helps them understand the timing and persistence of the effects.

Parallel Trends Test:

- To strengthen the causal interpretation, the authors test for parallel pre-trends between treatment and control groups.

- This ensures that the political outcomes were following similar trajectories in the counties prior to the local newspaper exits.

Figure 4 shows the estimated effects of local newspaper exits on political polarization and small party vote share. In the elections leading up to the local newspaper exit (-2 and -1), the figure shows that the treatment counties (those that experienced an exit) and the control counties (those that did not) were following very similar trajectories in terms of both electoral polarization and small party vote share. The effect estimates for the election immediately following the local newspaper exit (labeled 1) show a clear increase in both electoral polarization and small party vote share in the treatment counties relative to the control counties. Looking at the effects for the election two periods after the exit (labeled 2), the figure demonstrates that the polarizing impacts of the local newspaper exit persisted and even grew over time.